The European Union finds itself in an increasingly threatening international arena while its Common Security and Defence Policy continues to have serious deficiencies. Surmounting its weaknesses must be a top priority to gain strategic autonomy in handling security threats. But underinvestment and lack of coordination are difficult challenges to overcome.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has drawn the EU into one of its most serious geopolitical threats in its history. Amid this situation, the EU adopted a new Strategic Compass in March 2022; a document that develops an action plan for the next decade with ambitious goals in its Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), aiming to turn the Union into a more efficient security provider. However, such decisiveness must match resources. The CSDP has been historically characterised by expectation-capability gaps, underinvestment and intergovernmentalism, which reduces the international actorness of the EU as a soft power with very little geopolitical influence in security and defence affairs.

This lack of military power of the EU member states has been the result of continuous underinvestment and lack of integration in security and defence matters since the Cold War period. As a result, many conflict-resolution and prevention missions under the CSDP were a failure due to a lack of concise decision-making capacities, delays, and failure to respond, mostly caused by conflicting interests between member states. One example is the EUTM Mali training mission for the Malian government troops where the Council of the EU failed to issue any plans for military action despite having monitored the crisis for more than a year. When it decided to establish the training mission in 2013, France had already intervened, and most of the Malian government forces had by this time joined the battle against Al Qaeda alongside the French soldiers.

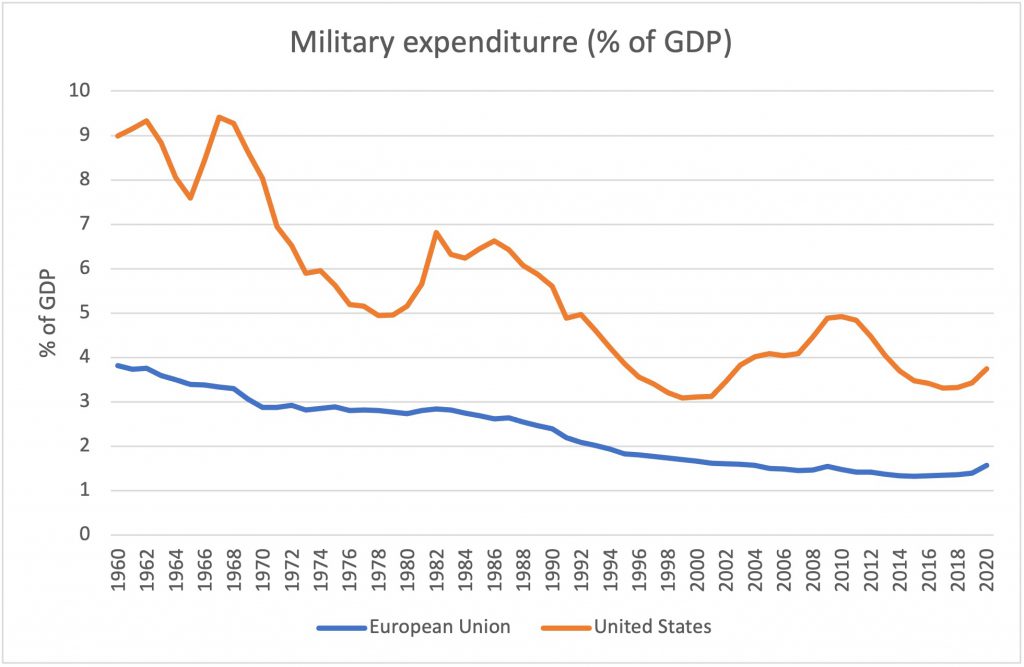

Almost one decade later, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has once again revealed the lack of strategic autonomy of the EU. The EU has been shown to be extremely dependent on US support for key military resources. In fact, European states have struggled to supply Ukraine with heavy weaponry, and the US has provided most of the military assistance to Ukraine through massive support packages. The following graph represents how since the Cold War years the US has spent overall more on military resources than the EU, which also evidences the existing unbalance in the current conflict, where the US has more power than the EU to provide military aid.

Figure 1: military expenditure (% GDP) in the US and EU. Source: World Bank (2022)

Nevertheless, the EU was a key player throughout the full-scale invasion, which started in 2022, by imposing sanctions against Putin’s revisionist regime, and providing financial and material aid to the Ukrainian army including, for the first time in its history, military resources via the European Peace Facility. Such actions may give the impression that we are witnessing a new era of European security, marked by a new impetus to increase its power and autonomy in defence affairs. The High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, reflected the current situation as a turning point for the EU’s responsibility as a security provider:

-

“The threats are rising, and the cost of inaction is clear. The Strategic Compass is a guide for action. It sets out an ambitious way forward for our security and defence policy for the next decade. It will help us face our security responsibilities, in front of our citizens and the rest of the world. If not now, then when?”

Josep Borrell, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (March 2022)

With this justification, the Strategic Compass, set out in March 2022, calls for an action plan that involves better coordination and integration at the Union level, with the creation of an EU Rapid Deployment Capacity consisting of up to 5000 troops and the promotion of a rapid and more flexible decision-making process in EU civilian and military CSDP missions. It also aims for a substantial increase in member states’ defence expenditures, and to further enhance partnerships with NATO, the United Nations, and other key partners such as the US and the UK, while ensuring the EU’s strategic autonomy. Moreover, the Strategic Compass explicitly refers to Russia as an aggressor state for the first time, whose objective is to establish its influence in the post-Soviet territories through the means of force and by perpetrating violations of international law.

Despite these objectives, the EU still faces several challenges in terms of an integration of its security and defence policy. Apart from the lack of expenditure, there is a lack of military coordination and mobility among national European armies, which hinders operations taken at the Union level. In fact, different strategic cultures of member states and competing defence industries have led European governments to prioritize national solutions at the expense of collective projects. This has led to huge gaps between overall military resources of member states and thus the Union’s collective capabilities, which remain very low. Moreover, political consensus is difficult to find in an area as important as security and defence. Most of the time, efforts to rationalise and optimise defence through collective action end up falling into ideological disputes over national sovereignty. These debates go far back into history, when the project of a European Defence Community, aimed to merge the armies of the six founding members into a single European Armed Force, failed in 1954. Ultimately, the deeply nationalist Gaullist deputies of the French National Assembly refused to ratify this agreement.

Overall, the war in Ukraine has revealed once again the Union’s vulnerabilities in the areas of security and defence, which it must surmount if it is to change its “bystander” status. The prospects seem good now, though, and the EU’s current agenda calls for an increasing collective action of the EU to effectively combat external threats, among which the Russian aggression is now at the top of that list. Nevertheless, long-term success in increasing such power will require an ambitious vision by the EU member states to rationalize European defence, integrate its many national and intergovernmental processes, and eliminate redundancies, with the objective of attaining maximum efficiency of their military resources and capabilities. The EU does not only require more defence spending, but better defence spending. This success will depend ultimately on the commitment of EU leaders to act in favour of a collective defence strategy. Such commitment is clearer in current times, when a common enemy threatens our territorial security, but not as clear in the long-term evolution of the geopolitical landscape, which is as unstable and unpredictable as the decisions of an unscrupulous dictator.

About the author

José Eduardo Seemann González

José Eduardo Seemann González is currently studying a dual Bachelor in International Studies and Law at the University Carlos III in Madrid. He completed an exchange year at the University of Vienna in 2022, during which he focused on the field of European Union studies. He is particularly interested in the history and politics of the post-Soviet space, especially in relation to nationalism and identity, frozen conflicts, and the phenomenon of quasi-states in the area.

Cover Image: Unsplash